A few weeks back I was taking a walk during my 10 minute break at work on the Sony lot in Culver City, California and spotted this photograph on the wall. The photo was of a 1937 recording session for Dimitri Tiomkin’s Oscar-nominated score for “Lost Horizon”. There were a few things that particularly struck me about it. The one that made me want to take my phone out and snap a picture was the one woman in the center of the photograph – the only woman in a sea of men. I’d never seen a picture of her in a studio setting, but I knew that face.

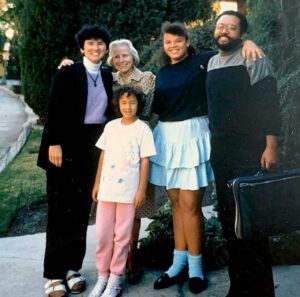

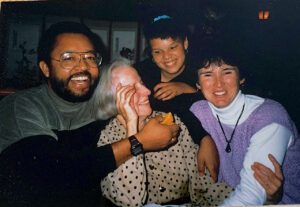

Virginia Majewski blessed me beyond measure when my cello was accidentally run over and destroyed when I was 14. In the ‘90s she often shared a stand with my father in the studios, and upon hearing this story, she invited my family over to her home in the Hollywood Hills so I could “try out” a cello she had in her basement. It was an old German factory cello and it became the cello that I played through my junior year of high school. From then on, my parents would drive me to Virginia’s for a visit and a lesson every month or two.

She was a consummate musician and although she was a violist and I a cellist, she had an immeasurable amount of knowledge, experience and wisdom that she imparted to me and was totally applicable to the cello. In a time where women were not welcome in symphony orchestras, it was difficult to build a career as a classical violist. The studio world was a little more progressive, but as the picture clearly shows, “little” is a bit generous.

Despite the challenges and blatant sexism of the 1930s, Virginia found success in Hollywood when she became principal viola for the MGM orchestra. This kickstarted her career and subsequently opened the door to countless opportunities playing on films and in studio ensembles accompanying many of the world’s most beloved artists including Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, and Nat King Cole.

Virginia came to be respected by composers and musicians alike. British conductor Leopold Stokowski once wrote, “I have never heard such wonderful playing with such a large and beautiful tone”, and American film conductor and composer Bernard Herrmann insisted that her name be listed in the credits for the 1951 “On Dangerous Ground” for playing the viola d’amore solo he composed.

Truthfully, I wasn’t aware of what an incredible trailblazer Virginia was before writing this. I knew she was well-respected and had often played chamber music with the likes of violin virtuoso Jascha Heifetz and cellist Gregor Piatigorsky. I knew she was an incredibly thoughtful and giving person, as many musicians today still cherish the small portable folding scissors she would gift her colleagues.

I knew she was someone who had welcomed my father, an Afro-Latino man, into the studio world and offered him wisdom and friendship. I knew she was strong. I knew she was successful. I knew my parents loved and respected her. I knew she was an electric woman at 84, so I can imagine she was even more of a force to be reckoned with in her 30s. I have always called her my angel.

After a few years of visits and lessons, Virginia brought out another instrument: an older, finer cello that felt like what I imagined an old Italian million-dollar instrument would feel like. It had a lot of scars and interesting surgeries, but the sound was like nothing I’d played before – it was far richer and warmer. She told us the story of the cello and how it was left to her by her beau, a Russian cellist who I’ve only ever heard referred to as Mr. B. She allowed me to play on that cello throughout my time as a student at the Idyllwild School of Music and the Arts.

The week of my 16th birthday, Virginia suffered a fall. I remember visiting her bedside in the hospital. It was there in that hospital room that she told me she wanted me to have the cello, accompanied by a beautiful Hill bow. I named the cello Lola, and it became my partner throughout college and successful auditions with the Chicago Symphony’s fellowship program, the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, New West Symphony, Santa Barbara Symphony, and countless other amazing musical adventures.

Today I sit and play in the exact same sound stages and concert halls that Virginia sat and played in, and in many ways it is thanks to her generous gifts and kind-hearted, masterful mentorship.

Knowing her was both a gift and a blessing. Happening upon this picture that day made me stand a little taller. The image of her, sitting in the front of the orchestra leading her section, surrounded by all those men, with her style, class, and her feisty personality I know so well humbled me and filled me with gratitude. I wish I could share with her what my life has become. I wish I could thank her for paving the way for female musicians like me.

I’ve always said she was my guardian angel, but seeing her in this picture and learning more about her through writing and researching this piece has made me feel that she’s not only been guarding me, but guiding me all along. She was truly a badass, and this photo not only reminded me of that, but gave me a new appreciation and admiration for her and her legacy.

Thank you for sharing this inspiring story of art and love. It absolutely made my morning. You and your family clearly exuded love as she did and blessed each others’ lives. I felt I could hear Bach’s beautiful prelude suite no. 1 as I read your story. Thank you again.

Thank you so much! Reading your comment made my morning! She was truly incredible and I am honored to be a small, living part of her legacy.

You brought tears to my eyes with your personal recollections of Virginia. I knew her through our mutual friendships with orchestrator Al Woodbury and his wife, Jeanne, and Johnny Green. Before I even met her, she asked Al (who was one of Johnny’s orchestrators for nearly 20 years) to give me the few studio acetate discs she had from the collection of Mr. B: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constantin_Bakaleinikoff

Virginia was a particular favorite of Johnny’s, who hired me as his archivist and became a very close friend over a period of 15 years. You’ll see Virginia right up front in those M-G-M Concert Hall shorts that Johnny produced and (with one exception) conducted. M-G-M Stage 1 was Virginia’s professional home from 1939 until Metro broke up the studio orchestra and dispensed with Johnny’s services in 1958, and they all became freelancers.

We talked a lot about her time at M-G-M. Some of her earliest work there was on the scoring sessions for The Wizard of Oz in the spring or summer of 1939. As she told me, she arrived after the playbacks had been recorded and shot months earlier, so she’s not on those tracks.

Thanks again for this wonderful reminder of a wonderful person we were both fortunate to know.